Want a Break from the Ads?

“I’m not willing to contribute my life’s work to an experiment that I don’t feel fairly compensates the writers, producers, artists and creators of this music” Taylor Swift (Sullivan). Swift has made it clear to the music industry her negative opinions on streaming services, specifically Spotify. Swift’s issues with copyright laws and licensing rights pushed her to remove her entire discography from Spotify shortly after dropping her album 1989, only to return back on Spotify in 2017 (Klein). Her advocacy for artists rights against the issues of streaming services are widely agreed amongst artists and songwriters within the music industry. After all, as digital music on the internet started to grow, there was a decline in physical sales (CDs, records, etc…) that left artists with very few options to produce income. Along with the rise of illegal online distribution of music, or piracy, artists were seeing virtually nothing in their pockets, simultaneous to the fall of the music industry. Once the crisis of piracy was averted by the introduction of the popular music streaming service Spotify, it took the world by storm, allowing millions of songs to be listened by anyone at any time. While Spotify may have originally saved the music industry from piracy, it is now slowly killing artists stream by stream.

Before the internet became widely used in the 1980’s and 90’s, music consumption was mostly done through live performances, radio broadcasts, and tangible copies. Listening to music was simpler then. It was all physical through concrete objects like records, CDs, vinyls, etc. As well as live physical experiences and moments such as concerts, open mics, and the radio. Being able to support their favorite artists directly by owning their music created a more intimate and personal relationship between the consumer and the artists. The physical action of buying a physical CD in stores or physically listening to live music while driving to work or seeing the artist on stage, gave consumers not only a relationship and an ownership, but an experience to music. As for artists, this created a deeper connection to their job and the fans they are affecting with their music. Concerts and music festivals provide an opportunity for artists to engage with their fans on a personal level, whilst generating revenue through ticket sales and creating a platform to promote physical music sales (“Are Digital”). This led to compensation being simple, as CDs and merchandising purchased from artists “provide[d] a higher revenue stream for musicians compared to digital sales” resulting in a higher profit margin than stream royalties (“Are Digital”). However, with the rise of the digital age, artists lost the value of their music as listeners shifted from physical attributions to their artists, to listening to their music online.

The music industry started to change with the expansion of the internet, as streaming music online became more accessible, shifting the way a consumer listened to music. As the internet became more ingrained in people’s daily routines, music found its place within its digital realm. With the internet making access to information easier than before, accessing whatever music you wanted became much easier with piracy, “the unapproved copying of copyrighted material, that is then offered for sale on the “gray” market at significantly reduced price or for free” (“What Is ‘Piracy'”). Pirate file-sharing platforms like Napster and Limewire (in the US) and Pirate Bay (in Europe) arose in 1999, allowing people access to whatever music they wanted, whenever they wanted. This came as a huge shock to the industry, as the availability of free products and value-erosion of recorded music resulted in customers buying fewer products from artists directly. Piracy offered consumers an amazing experience of getting all the music they wanted for free, but it was not perfect. With piracy, songs took minutes to download, listeners had to be wary of viruses, and it was very cumbersome (John). As troublesome as this seems to the consumer, artists mainly took the brunt of the downsides to piracy. Many artists suffered from piracy sites as none gave any artists recognition or compensation for their music, and therefore robbed them of their work. Not only did artists suffer, but so did the music industry. The rise of Napster “…began the cataclysm that caused worldwide revenues to decline from a peak of 27 billion dollars, in 1999, to 15 billion, in 2013” (John). As listeners stopped buying music directly from artists and opted for piracy, the music industry plummeted, leaving artists wary and concerned about their career. Artists’ worries over their financial stability increased as they witnessed the music industry’s decline, realizing that not only are they not receiving money for their work, but the rest of the industry is not either; further intensifying their concerns about the longevity of their careers. Every party in the music industry was panicking, worrying about the future of music and scrambling for a response to piracy.

The music industry was in a dire need of a solution to compensate artists; unbeknownst to them however, Apple was on the verge of a breakthrough. In October of 2001, the iPod, Apple’s first generation MP3 player, was released. Rather than being a heavy compact disc player as a record or a CD, the iPod gave listeners a sleek and easy way to access their purchased MP3 tracks in Apple iTunes. iTunes was a music player, music library, and online radio broadcaster that required listeners to purchase in order to use. iTunes was also only able to be used on Apple devices, limiting outside platform users. Within two years of launching the download service in 2001, iTunes music store had sold over 500 million records and by 2012, 60% of digital music sales globally were made through Apple’s iTunes music store (Swanson). However, this surge in digital sales led to a decline in physical music sales, which reshaped not only consumer habits, but also artist habits. This turning point to the internet led artists to begin making more money from “touring, publishing, and merchandising” (Huffman). Despite iTunes solving the issue of listening to legal music online, it was not free. As piracy was still available to consumers as the free version of iTunes, people tended to opt for the free option, leaving the issue of artists being uncompensated, unsolved. The uncertainty of music distribution intensified the fears and worries of not only artists, but the entire music industry. However, the introduction of Spotify suddenly altered the future of how music was consumed (John).

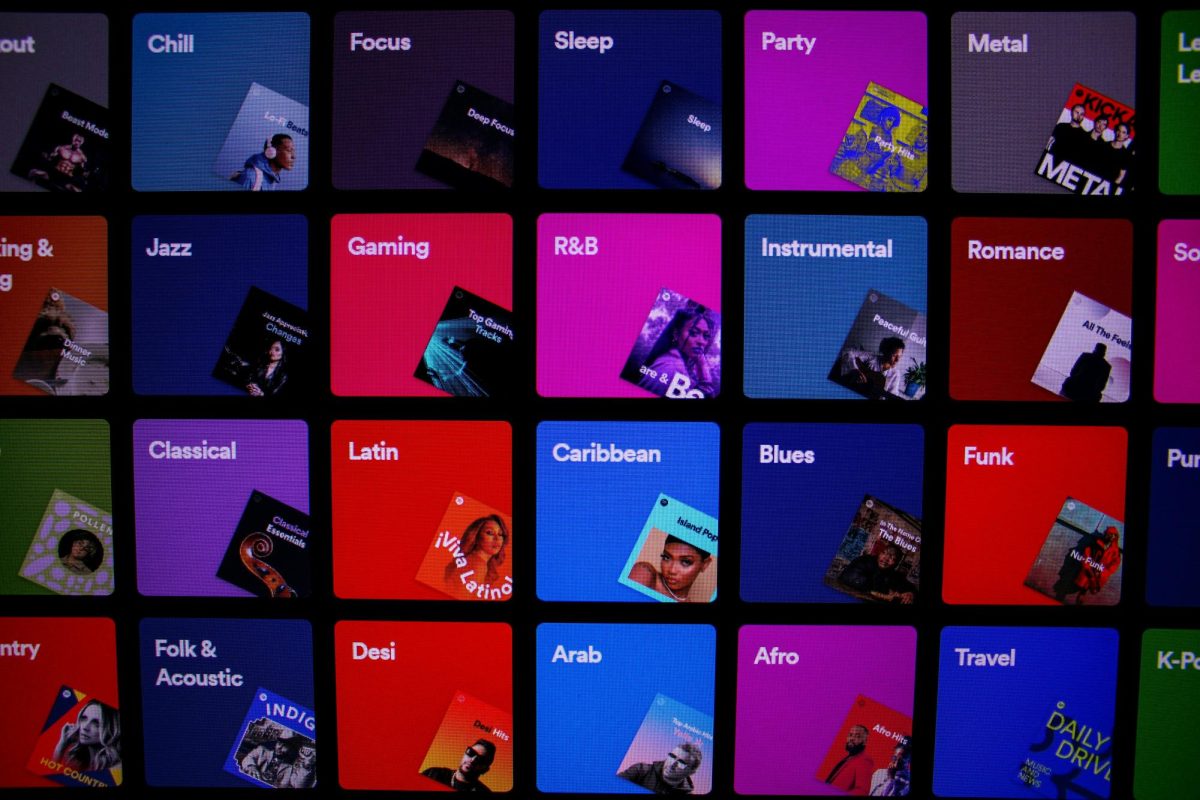

With piracy killing the music industry, Spotify launched in 2008 saving artists from piracy as the first free legal music streaming service in Sweden (Swanson). Daniel Ek, the founder of Spotify, saw an opportunity to use modern technology to create a free and legal music streaming service that would surpass piracy. Ek thought “…Napster was such an amazing consumer experience, and [he] wanted to see if it could be a viable business” (John). As tame as it may sound, this idea was heavily rejected and opposed by record labels and music rights owners. With piracy taking the world by storm, the idea of ‘free’ music was immediately associated with piracy, causing a lot of doubt from major companies in Spotify’s business model (John). All of the issues consumers had with piracy, Spotify countered and provided listeners a better service that worked faster than the standard piracy site. Spotify offers a vast catalog of music from various genres, artists, and labels with which users can access millions of songs and albums. Spotify became known uniquely for the addition of the playlist: where users can add any songs of their choice to their own personal tracklist. With the help of Spotify’s user-friendly interface on various platforms, users can search for specific music, listen to other users playlists, create playlists of their own, follow artists, and discover new music. Spotify’s recommendation system is a key feature that suggests music to users based on their listening history, preferences, and behavior. Spotify collects a vast amount of data on user preferences, listening habits, and behavior to analyze user data, provide personalized recommendations, and give insights into music trends. At the time, Spotify was the only legal streaming site that operated and offered users the choice of signing up for a free account, ‘freemium’, or premium subscription tiers. The free tier is supported by radio-style and visual advertisements and limitations on features like offline listening and skipping tracks. The premium tier offers ad-free listening, offline mode, higher audio quality, and other premium features for a monthly subscription fee. Ek’s goal with the ‘freemium’ accounts was to encourage more consumers to convert to paying memberships, and the company’s uniquely high percentage conversion rate of 43% in the first quarter of 2022 suggests his plan worked (Trainer). After finalizing the site and obtaining music rights, Spotify launched in Sweden in 2008. Once Spotify became one of the largest digital revenue generators in Europe, it entered the U.S. market in 2011 (Swanson). Spotify became known for its convenience to the consumer, as iTunes was still purchase-only. Listeners who were not inclined or had the luxury to buy a new album or song, found comfort in Spotify as their ‘freemium’ option was a big driving point. This made it easier to be musically adventurous, as in the past, that was a privilege (Robinson). When consumers had to pay for the music they wanted to listen to, the ability to experiment with genres and new music became difficult. Consumers took the financial risk of purchasing the track or album blindly, with no knowledge whether they would like it or not. Spotify assisted the solution for online piracy, becoming another legal option when it comes to listening to music online, which many artists believe is important to the aid of the music industry. Spotify grants listeners the liberty to explore music genres, while serving as a pivotal platform for artists to strengthen their exposure (Bakare). Not solely artists but Merck Mercuriadis, the CEO and founder of Hipgnosis Songs Fund, also believes that “Streaming has saved the music business by making it more convenient for people to once again consume music legally rather than through illegal file sharing” (Bakare). Spotify became a breath of fresh air in the music industry and offered relief to the crisis of piracy, but this did not last long.

An unforeseen problem with Spotify as a service was its royalties policy being unclear and needing transparency. Royalties are incredibly low for songwriters and musicians as artists are getting paid an estimate of less than $0.0049 cents per stream; resulting in many of these artists finding it difficult to make a living (Sullivan). Not only is the pay inadequate, but a direct number of how much an artist is getting paid is unclear, as Spotify does not discuss paying royalties with musicians directly. Instead, artists go through labels or distributors, which are then responsible for making pre-negotiated rates on their royalties (Swanson). These pre-negotiated rates are decided by labels, giving labels the decision on how they want to parcel these payments out to artists. With how much money that needs to be split between Spotify, labels, fees, and eventually artists, it becomes unclear to artists how much money they are receiving from streaming. It is also unknown what licensing agreements Spotify had signed with record labels during the app’s launch, as nondisclosure agreements were signed by all parties. This illustrates that the lack of transparency did not start within the agreements made with artists, but in the foundation on which Spotify was built from. Due to Spotify being required to pay out a majority of its revenue in fees, 97.9% of artists will not receive any income from album sales because the label uses all royalties to cover its initial expenses (Swanson). The money generated from artists’ streams are absorbed by Spotify to pay its fees to record labels and copyright holders, and to cover initial costs such as recording, production, marketing, as well as distribution of the music. Due to Spotify’s financial obligations and practices to pay these out to record labels before artists, artists will not be directly benefited for their music until said costs are paid. Paying off initial expenses and fees took a long time with Spotify’s business model as the company barely made a profit before 2013 as they paid out so much of its revenue in fees (John). If artists are not at Drake, Taylor Swift, or The Weeknd’s level of streams or listeners, it becomes very difficult to make a living off of Spotify. Ayanna Witter-Johnson, a small, independent self-releasing singer, songwriter, cellist, and composer with 4,268 monthly listeners, found many struggles during COVID as the “…disappearance of [her] primary income from live performance…” resulted in her streaming income becoming more important (Bakare). Witter-Johnson expresses that “…the majority of the income from streaming doesn’t trickle down to independent artists” and that the “…current split of income is unfair, dangerous and needs to change…” (Bakare). Currently, artists with more streams get more money than smaller artists who do not have as many. However, this does not mean that those smaller artists should not have the ability to make a living wage off of Spotify. The music industry has changed drastically with the addition of Spotify, resulting in a change in how artists get compensated. With the changes being made in the music industry, artists believe that the “royalty rates need to be reformed to reflect the way music is delivered today…” (Bakare). The music industry is unfazed by Spotify’s royalty plan, but this same plan is causing detrimental effects to the artists. Spotify’s low and unclear royalties, which are notably insufficient for musicians and songwriters, make up some of Spotify’s negative impacts on artists

Copyright laws have not kept up with the digitalization of the music industry, causing artists to lose trust in streaming companies like Spotify. Various streaming services ignore copyright laws by neglecting to acquire mechanical rights, “the right to reproduce a piece of music onto CDs, DVDs, records or tapes”, causing many worries and issues for artists (“What Is the Difference”). Many artists fear there is minimal protection without copyright to music, leading to the relationship between the company and artists to become counterproductive (Bakare). In hopes of resolving this issue, the Music Modernization Act was created by Congress. The Music Modernization Act (MMA) is “a copyright royalty board, and a collective body to collect mechanical royalties from streaming companies on behalf of musical publishers and songwriters” (Huffman). The MMA intended to develop a blanket licensing system for music streaming services to ensure that music licensing regulations reflect the digitalization of the music industry and its developments (Huffman). The MMA sought to help the music community by providing a more transparent, efficient, and updated approach to music licensing and artist compensation. This act was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump in 2018 and is widely supported by the music industry, including both music publishers and songwriters themselves. “Spotify specifically praised the legislation, claiming the MMA will allow songwriters to be compensated for creating works they are passionate about” (Huffman). This praise of legislation from Spotify is a step in the right direction towards fixing Spotify’s inner complications with copyright laws. However, the MMA could be interpreted differently. The following interpretation is vehemently opposed by songwriters and music publishers as it can be read as ‘failing to compensate songwriters appropriately for the work they create and copyright’ (Huffman). Deciphering the MMA like this inherently negates the goals and objectives the MMA strives to achieve for artists, bringing them back to square one. Issues with copyright laws within Spotify have grown large enough to create acts of legislation, which still end up failing to aid artists and songwriters. The survival of the music industry as a whole is threatened by the inner copyright issues within Spotify, and the lack of legislation that adequately protects artists’ rights; which worsens already-existing tensions between creators and streaming services. Artists are left to face low income and less control over their creative works, meanwhile the music industry continues to ignore the pleas of the artists as it does not affect them.

Streaming services like Spotify are actively harming the music industry, even though they may have initially saved it from piracy. While Spotify does have many flaws, Spotify is not evil. There are benefits to Spotify that do contribute to artists, but not in tangible ways, such as getting exposure to get discovered and to promote tours and merchandise. Nevertheless, none of these small wins consider the fact that Spotify and similar streaming services are still harming artists careers, and soon the future of the music industry. Without any action put behind change to fix this, it will only kill the motivation of artists to continue creating the music they love. While smaller artists are mainly harmed by these issues, even larger artists such as Taylor Swift feel the same way. The efforts from all stakeholders, including streaming platforms, record labels, and consumers, are needed to ensure a sustainable and equitable future for artists. If we do not take care of the artists, it will leave a world devoid of experience, memories, and expressions of love.

Works Cited

“Are Digital Music Sales Replacing Physical Music Sales?” Mogul, 18 Nov. 2023, www.usemogul.com/post/are-digital-music-sales-replacing-physical-music-sales#:~:text=Purchasing%20physical%20copies%2C%20such%20as,digital%20sales%20or%20streaming%20royalties. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

Bakare, Lanre. “The Music Streaming Debate: What the Artists, Songwriters and Industry Insiders Say.” The Guardian, 10 Apr. 2021. The Guardian, www.theguardian.com/music/2021/apr/10/music-streaming-debate-what-songwriter-artist-and-industry-insider-say-publication-parliamentary-report. Accessed 3 Feb. 2024.

Huffman, Anna S. “What the Music Modernization Act Missed, and Why Taylor Swift Has the Answer: Payments in Streaming Companies’ Stock Should Be Dispersed among All the Artists at the Label.” The Journal of Corporation Law, vol. 45, no. 2, 2020, p. 537+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A622269266/AONE?u=mlin_c_bancsch&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=163ad5dd. Accessed 31 Jan. 2024.

John, Seabrook. “Revenue Streams.” The New Yorker, vol. 90, no. 37, 24 Nov. 2014, p. 68. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A392474495/AONE?u=mlin_c_bancsch&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=25c2e66d. Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

Klein, Ashley N. “Taylor Swift Music Icon and Copyright Gamesman?” Landslide, vol. 16, no. 2, Nov.-Dec. 2023, p. 34+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A780928937/AONE?u=mlin_c_bancsch&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=6ec88ea5. Accessed 6 Mar. 2024.

“Music Streaming Services Are on the Cusp of Major Structural Change.” Goldman Sachs, 31 July 2023, www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/page/music-streaming-services-are-on-the-cusp-of-major-structural-change.html. Accessed 12 Feb. 2024.

Ovide, Shira. “Streaming Saved Music. Artists Hate It.” New York Times, 22 Mar. 2021. New York Times, www.nytimes.com/2021/03/22/technology/streaming-music-economics.html. Accessed 30 Jan. 2024.

Robinson, Kristin. “15 Years of Spotify: How the Streaming Giant Has Changed and Reinvented the Music Industry.” Variety, 13 Apr. 2021. Variety, variety.com/2021/music/news/spotify-turns-15-how-the-streaming-giant-has-changed-and-reinvented-the-music-industry-1234948299/. Accessed 6 Feb. 2024.

Sullivan, Mikaela. “Which Artists Have Earned the Most from Spotify?” Top Dollar, 10 Mar. 2021, www.accrediteddebtrelief.com/blog/which-artists-have-earned-the-most-from-spotify/. Accessed 12 Feb. 2024.

Swanson, Kate. “A Case Study on Spotify: Exploring Perceptions of the Music Streaming Service.” MEIEA Journal, vol. 13, no. 1, 2013, p. 207+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A356143089/AONE?u=mlin_c_bancsch&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=e9e847e4. Accessed 28 Jan. 2024.

Trainer, David. “Spotify: The Music Is Ending for This Once High-Flyer.” Forbes, 7 June 2022, www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2022/06/07/spotify-the-music-is-ending-for-this-once-high-flyer/?sh=108e6ddb9841. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

“What Is ‘Piracy.'” The Economic Times, economictimes.indiatimes.com/definition/piracy. Accessed 7 Mar. 2024.

“What Is the Difference between Performing Right Royalties, Mechanical Royalties and Sync Royalties?” BMI, www.bmi.com/faq/entry/what_is_the_difference_between_performing_right_royalties_mechanical_r#:~:text=The%20%E2%80%9Cmechanical%E2%80%9D%20right%20is%20the,the%20publisher%20to%20the%20composer.). Accessed 6 Apr. 2024.