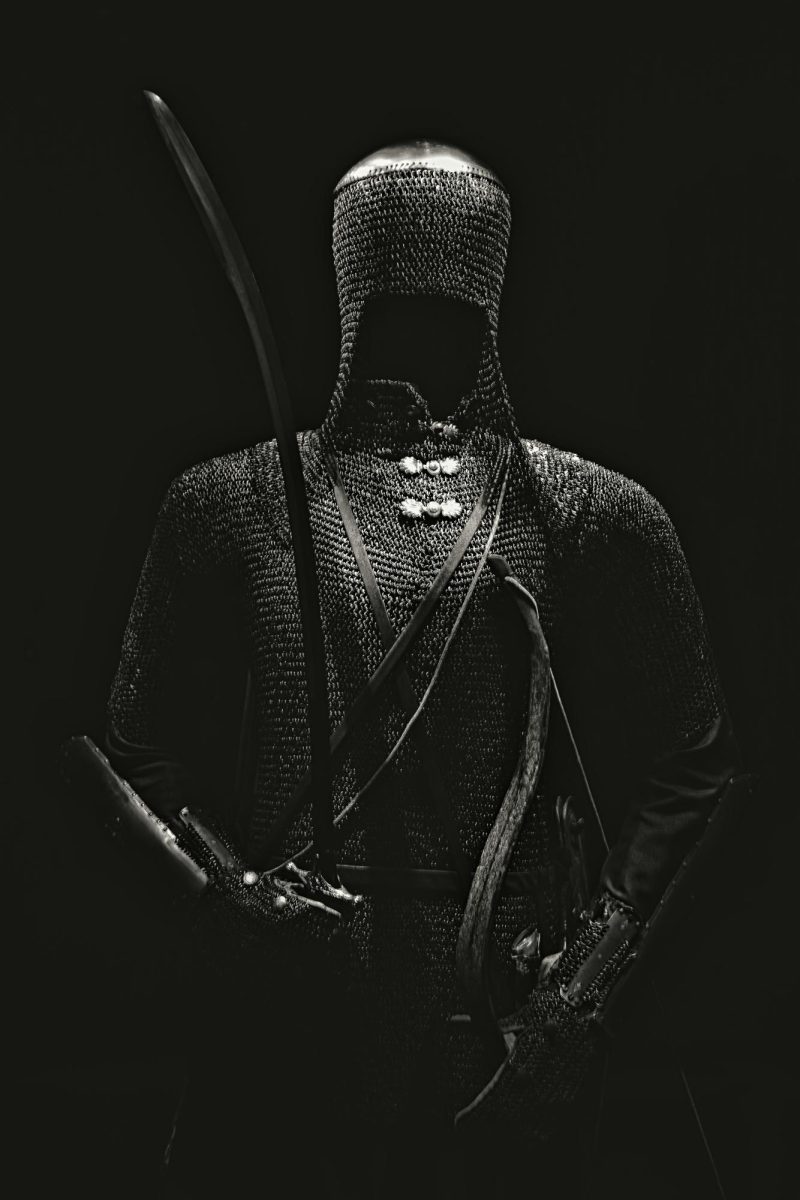

Beowulf is an ancient text about a warrior named Beowulf. Throughout the book, he goes on many dangerous exploits always with the livelihood of his people, the Geats, in mind. After a monster named Grendel captures and kills a large number of warriors, Beowulf steps in to save the day. After a brutal fight, he manages to kill Grendel, restoring peace to the warriors of the land. Though the death of this monster overjoys many people, Grendel’s mother is sent into a rage. She rules over a shadowy marshland and continues her son’s murderous legacy by capturing and killing more warriors. So, Beowulf bravely ventures into her realm, where the fight to end all fights ensues. Compared to Seamus Heaney’s version, I prefer Maria Dahvana Headley’s translation. Although Heaney is certainly a poetic and talented writer, Headley’s version is better because she offers a highly unique perspective and writes in a much more emotive way.

Is Grendel’s mother truly a monster? Or, is she just someone dealing with perhaps the most human experience possible: deep, profound grief? Grendel’s mother is never even named beyond her relation to her son, whose brutally ripped-off arm she treasures after his death. Her descriptors vary widely: in line 1497, Headley refers to her as “She who’d ruled these floodlands proudly” whereas Heaney calls her “the one who haunted those waters” (line 1497). These have very different connotations. Headley’s brings to mind imagery of a strong, warrior-minded queen, someone with honor and dignity. Heaney’s, on the other hand, immediately makes Grendel’s mother into a monster, a witch, someone to be feared. In another part of the text, she is described as both having “fingernails” (line 1503) by Headley, and “savage talons” (line 1504) by Heaney. Again, Headley is more sympathetic towards the plight of Grendel’s mother. “Fingernails” is a very neutral word, especially compared to “savage talons”. Heaney, however, leans into presumed negativity about Grendel’s mother and wants the reader to sense that as well. Headley’s translation is more humanizing. This is a very unique take on Grendel’s mother’s story: monster, or just someone in a bad situation? Because this way of thinking contradicts the typical narrative, it becomes much more interesting and engaging.

Headley’s translation of the text also conveys much more emotion than Heaney’s. For example, in line 1498, she refers to Grendel’s mother’s way of ruling her marshy domain as “ferocious, tenacious, rapacious.” Heaney, on the other hand, prefers to call her she “who had scavenged and gone her gluttonous rounds” (line 1498). Even though this particular wording is strong and disarming, it is also very surface-level. “Scavenging” and being “gluttonous” are both words that only describe what someone does outwardly, but not their inner, deeper, emotions. This is disappointing. To “scavenge” or be “gluttonous” can be something that is caused by profound, deep-seated (and honestly, more interesting) emotions and experiences. Heaney’s wording in the portion of the text glides over the motivation and emotion of this woman in favor of shock factor. Headley’s translation, on the other hand, shows much more emotion. “Ferocity, tenacity, rapaciousness:” These are all emotions. And not surface-level ones, either. They paint a striking picture of Grendel’s mother: a jaded woman, ruling her land with an iron fist and keeping her son safe by sheer force of will. While these emotions may be classed as “bad,” they certainly make for a much more interesting read. Additionally, in line 1503, Headley explains what Grendel’s mother wanted to do to Beowulf as his “dread fate,” while there is no such mention of Beowulf’s future or Grendel’s mother’s intentions in Heaney’s translation. This is surprising, seeing as Heaney had taken such an anti-Grendel’s mother stance up until this point that it frankly does not make sense as to why he would fail to include any line that fosters sympathy for Beowulf. Headley, who is usually much more neutral (or even positive) towards Grendel’s mother, still manages to see the other side through Grendel’s mother’s red-eyed fury. She makes the reader feel Beowulf’s terror and shock at a worthy adversary’s fighting spirit. This also ties into when Headley referred to Grendel’s mother as being “ferocious, tenacious, and rapacious.” Of course, a childless mother who is strong-willed, determined, and unafraid would have the motivation to hurt Beowulf. This adds a layer of real intrigue and an almost sadness to the text, something Heaney’s version lacks. If a reader were to skim through Heaney’s version, they would be able to pick up on most of the details: there is little depth in his writing. However, a reader skimming through Headley’s version would have to read actively to fully understand it because of the emotional depth of her writing.

Overall, it is made clear through this portion of the text that Headley’s translation is much more unique and emotional. This makes the text much more interesting and engaging to read because it makes the reader think: what would they do under those circumstances? Is Grendel’s mother justified in her actions? Is she even a monster? On the other hand, reading Heaney’s version, the reader sees the events at face value and is not forced to think beyond any preconceived notions they may have. Headley’s translation also challenges stereotypes and biases surrounding women. Allowing Grendel’s mother to be crazy because of her surface-level emotions is a lazy and antiquated way of writing a woman, and this is exactly what Heaney’s version offers. While Headley’s version does not give Grendel’s mother a name, which she only gets through her son, it gives her a life. It gives her motives and sympathy, reason and depth. All in all, I much prefer Headley’s version. Its fresh take on an ancient character is both interesting and entertaining, and its use of emotion is a breath of fresh air that makes the story much more modern and engaging.

Photo by Martin Zaenkert on Unsplash