The Sirens Heard From The Sweatshop

April 15, 2022, marked the beginning of Passover, a Jewish holiday that celebrated the biblical story of Israelities who left Egyptian captivity and passed through the Sea of Reeds. The holiday celebrates the liberation of Jewish people, and by extension the ideas of freedom and liberty. Passover lasts for seven – sometimes eight – days, and one tradition of Passover is the seder dinner, where various foods, each having a symbolic meaning, are served.

In the early twentieth century, many American Jews began to hold seder dinners to show solidarity and allyship for social justice causes. A well-known dinner was the 1969 Freedom Seder, in which people from all walks of life came together to commemorate the life of Martin Luther King Jr. “Jews and Christians, rabbis and ministers, black and white,” sat together, passing around matzo (flatbread). To guide the service, they read a Haggadah (seder text) written by Authur Waskow, a Jewish author and activist, that discussed police violence, freedom for all, and the removal of nuclear weapons. Throughout the seder, Jews, Christians, and others recited hymns in unity. The Freedom Seder was one example of Jewish involvement in human rights debates. Further, it provides vital context to ask: what is the history of Jewish involvement in social justice movements?

To begin, between 1880 and 1920, millions of Jews entered the United States. The majority came from Eastern European countries such as Russia and Poland. Like many immigrants, they came because they wanted better working conditions and to escape from the anti-semitic discrimination they were facing in their homelands. In Tsarist Russia the situation was especially dire. As it was difficult to obtain higher positions due to anti-semitism, many were accustomed to working in sweatshops that were “intensive manual labor while offering poor working conditions and low wages.” Soon getting fed up with this kind of treatment, a socialist organization called General Jewish Labour Bund arose, in 1897. Poor and middle class Jews united together to advocate for more rights within the working class and to fight against the “tsarist regime” who were avid supporters of capitalism. As the years continued, many Eastern Europeans fought advantageously for political and social liberation in Russia: by learning socialist literature and “a number of them had belonged to a variety of secret revolutionary circles.” However, with fighting for equality and more opportunities, increased violence arose in the form of pogroms and stricter regulation from the tsar.

In May of 1881, Tsar Alexander III of Russia had implemented a long list of laws that made the daily lives of Jews difficult. Jews could not access higher education, and it was a struggle for them to enter or exit their respective towns and villages. Further, to build generational wealth was a hurdle, as it was illegal for Jewish stores owners to hand over their businesses to their family members.

In addition to discrimination, Russian Jews were victims of violent massacres called ‘pogroms.’ Essentially, a pogrom is when rioters incite violence and turmoil with the sole purpose of eradicating or chasing off a marginalized group. In this particular case, on April 19, 1903, in Kishinev, a riot resulted in “forty-nine Jews…killed and more than five hundred injured. Seven hundred houses and six hundred businesses were destroyed.” The May Laws of 1881 and Kishinev Pogrom were not the sole contributors to millions of Eastern European Jews leaving for America, but in combination with discrimination, lack of opportunity, and constant struggles, many Jews felt that seeking a country like America would finially provide them libration and peace.

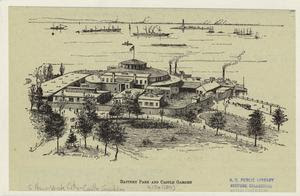

When Jewish immigrants arrived in America, they were hoping for a country with a more involved and responsible government, equality for and within the working class, and the free opportunity to flourish in the economy. The early 1900s was the peak era for the United States labor industry, especially in cities like New York. As a result, many Jewish immigrants who had established industrial skills sought the city for job opportunities; fortunately, upon arriving at ports like Castle Garden, employers were already seeking them.

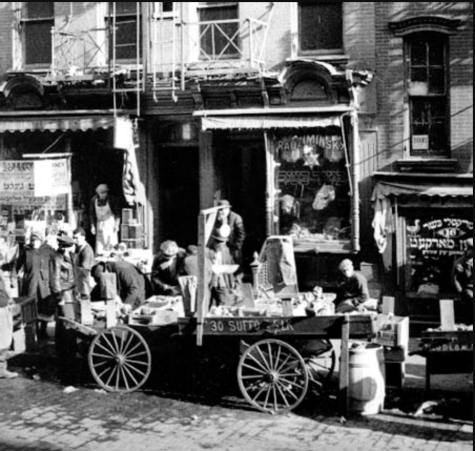

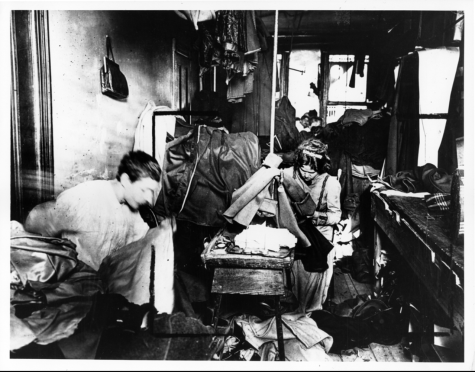

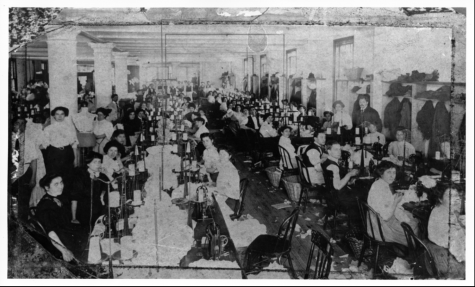

Although they had more accessibility to jobs, when arriving in districts like the Lower East Side—a predominantly Jewish community–many were disappointed in what they discovered. The district was known for its overcrowdedness, as it contained an abundance of factories and tenements. Most popular among the factories were garment buildings, where shirtwaist workers often made clothes in sweatshops that were “crowded, poorly ventilated, and prone to fires and rat infestations.” Workers had long shifts with low wages, and with a majority of them being women, dealt with misogynistic employers.

In fact, the garment industry consisted of “Jewish, Italian, and Native American women workers who formed respectively about 55, 35, and 7 percent of the women in the trade in New York.” The industry was dominated by Jewish women, because while living in countries Russia and Poland, many were expected to learn the trade of sewing and needlework. Moreover, the conditions of the garment sweatshops were similar to shops many Eastern European Jews worked in while living in their home countries. As a result, it caused shirtwaist workers to begin showing discontent for their employers, and speak amongst themselves about the possibility of a strike.

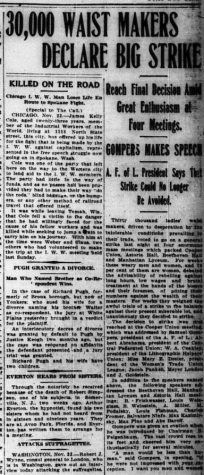

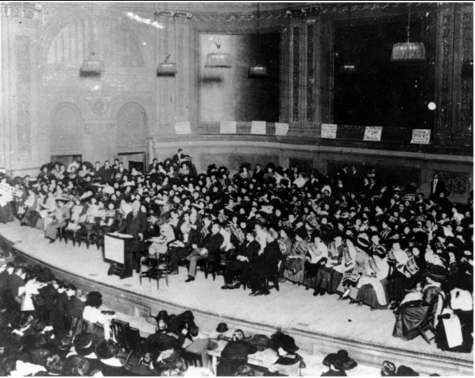

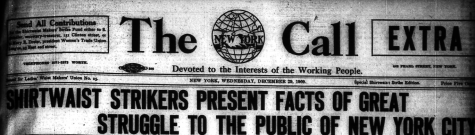

Finally gaining the courage, on September 27, 1909, workers from the Triangle Shirt Waist left their equipment and walked off the job. They were angry because their employer made the decision to not pay them after blaming workers for a dispute with the subcontractor. The Local 25- a union organization–officially declared a strike against the company, and afterwards, shirtwaist workers held demonstrations in front of the factory for three months. During that time period, more garment workers walked off from their employers, and eventually on November 23, 1909, a meeting, organized by “committee” union organizers, was held to determine whether or not a strike could be declared. The New York Call, a socialist newspaper, reported that around 30,000 shirtwaist workers were in attendance at the strike.

A particular moment that was captured was that of a Ukrainian-Jewish garment worker, Clara Lemlich. After listening to union organizers’ long winded speeches, Lemlich, who before the meeting had been “assaulted while picketing”, demanded to speak. She said, “I am a working girl, one of those who strive against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall or shall not strike. I offer a resolution that a general strike be declared–now.” With a plea, Lemlich’s speech represented the voices of the strikers, and the crowd cheered. Workers were tired of negotiating and were willing to sacrifice their livelihoods for a better future in the garment industry and that is how the 1909 Shirtwaist Strike began.

After Cooper Union, thousands of shirtwaist workers left their shops and joined labor unions, like the Women Trade Union League and International Ladies Garment Workers Union. In order to maintain organization, union organizers would assign an “chairman or chairlady” to individual garment factories that were on strike. Their jobs would be to come up with strategies that could educate the public and encourage other shirtwaist workers that were afraid to leave their jobs to join.

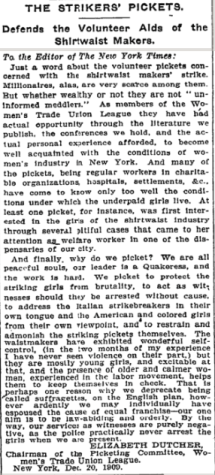

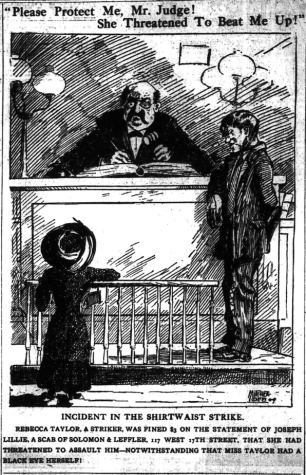

Additionally, because the season of the Shirtwaist Strike was during harsh winter, many immigrant workers struggled to provide for their families, without a job. Newspaper organizations like The Progressive Women or The New York Call would write about how strikers would starve all day in order to sell newspapers that would go into helping fund the strike. Or, the brutality and unjust arrests picketers would experience from police officers, and hired delinquents as they were protesting in front of their employers factories. Nonetheless, many of the women, who were predominantly Jewish, already had progressive and democratic beliefs ingrained into their culture, and were not willing to give up on the fight for better working conditions so the hardships continued.

One of the most important contributions that the 1909 Shirtwaist Strike had was the pioneering diplomatic tactics used to popularize the strike. Strikers picketed, sold newspapers, and included wealthy women in their picketing demonstration so newspaper outlets could track their events. Also, union organizers would attract media outlets by holding large meetings, such as the one held at Carnegie Hall on January 2, 1909, in which the main prerogative was for individuals from all social classes to stand against the mistreatment strikers received from police officers and employers.

The Shirtwaist Strike ended on February 15, 1910, and while it did not drastically change the labor system, The New York Call did report that “fifty-one factories had signed union negotiations and more than seven thousand strikers were returning to work”.

Furthermore, strikers actions led to several new protections that influenced the labor industry for many years, such as the Protocol of Peace, and set up a legacy of Jewish involvement in social justice work.

Based on the research presented, Jewish women played a vital role in the 1909 Shirtwaist Strike; because of their commitment to better working conditions and fundamentally, human rights, many became leaders in creating unity between the diversity of shirtwaist employees. What surprises me is the fact that all of these strikers so confidently and strategically declared their demands to employers during a time when women could not even vote. Many of these strikers went through, blood, sweat, and tears, to make the public aware of the injustices occurring in their workplace. And as history moves on and we learn about the suffrage movement and other human rights debates, familiar names appear, like Clara Lemlich, the girl whose voice ignited the strike. Lemlich worked her entire life, fighting for the rights of people. She spent time with the Wage Earners League to recruit members and promote the message of women’s rights. Further, she became a dominant member in the kosher meat boycotts of 1917. Ultimately, The Shirtwaist Strike of 1909 proved that when a woman wants to speak, she will.

Work Cited

Books

Edge, Laura Bufano. We Stand as One: The International Ladies Garment Workers’ Strike, New York, 1909. United States: Twenty-First Century Books, 2011, 45.

Epstein, Lawrence J. At the Edge of a Dream: The Story of Jewish Immigrants on New York’s Lower East Side, 1880-1920. United Kingdom: Wiley, 2007, 9-10.

Lorwin, Lewis Levitzki., and Levine, Louis. The Women’s Garment Workers: A History of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. United States: B.W. Huebsch, Incorporated, 1924, 149-156.

Weinstein, Bernard. The Jewish Unions in America: Pages of History and Memories. United Kingdom: Open Book Publishers, 2018, 47-48.

Websites

“Garment Industry History Initiative: A Partnership with the Leon Levy Foundation.” The Gotham Center For New York City History. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://www.gothamcenter.org/garment-industry-history-project.

Blatman, Daniel. “The YIVO Encyclopedia Of Jews In Eastern Europe.” Bund. Last modified July 30, 2010. Accessed May 14, 2022. https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Bund.

Brains Paul. “Introduction to 19th Century Socialism.” Washington State University. Last modified March 28, 2005. Accessed April 20, 2022.

https://brians.wsu.edu/2016/10/12/introduction-to-19th-century-socialism/

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. “Passover.” Encyclopedia Britannica, February 16, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Passover.

Deena Prichep. “In Freedom Seder, Jews and African Americans Built A Tradition Together.” National Public Radio. Last modified April 16, 2015. Accessed February 14, 2022.

Orleck, Annelise. “Clara Lemlich Shavelson.” Jewish Women’s Archive. Last modified December 31, 1999. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/shavelson-clara-lemlich.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. “Labor Movement in the United States.” Jewish Women’s Archives. Last modified December 1999. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/labor-movement-in-united-states.

“Sweatshop,” New World Encyclopedia. Last modified January 15, 2020. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Sweatshop&oldid=1030741.

Zauzmer, Julie. “The Freedom Seder: The anti-racism dinner party that changed American Judaism.” The Washington Post. Last modified March 29, 2018. Accessed May 14, 2022.

Images

A group of men and women Marching with Strike Signs. 1910 Estimated. Photograph. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archive. https://www.flickr.com/photos/kheelcenter/5279765808/in/album-72157625640787200/.

A group of women raise hands to volunteer for picket duty during the Shirtwaist strike of 1909-1910. 1909. Photograph. The Digital Public Library of America. http://search.openlibrary.artstor.org/object/SS7729539_7729539_1666900_CORNELL.

A meeting for Shirtwaist Strikers and their supporters at Carnegie Hall to celebrate the courage of strikers who had been arrested. 1910. Photograph. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives. http://trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu/slides/294.html.

Battery Park and Castle Garden. 1891 Estimated. Photograph. New York Public Library Digital

Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-0f43-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Garment Factory circa 1910. 1910. Photograph. Jewish Women’s Archive.

https://jwa.org/media/photo-of-large-garment-factory.

Lower East Side of New York City circa 1900. c.1900. Photograph. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/media/street-scene-on-lower-east-side-of-new-york-city.

Portrait of Clara Lemlich, leader of the Shirtwaist Strike of 1909-1910. 1910. Photograph. The Digital Public Library of America. http://search.openlibrary.artstor.org/object/SS7729539_7729539_1667867_CORNELL.

Portrait of Women Shirtwaist Strikers holding copies of “The Call.” 1910. Photograph. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archive. https://www.flickr.com/photos/kheelcenter/5279774588/in/album-72157625640787200/.

Russian May Laws, 1882. Photograph. Center For Online Judaic Studies. http://cojs.org/russian_may_laws-_1882/.

Sweatshop circa 1900. 1900. Photograph. Jewish Women’s Archive. https://jwa.org/media/photo-of-sweatshop.

Zipperstein J. Steven. Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History. Photograph. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/review/books-pogrom-kishinev-and-tilt-history-steven-j-zipperstein-liveright.

Newspapers

“30,000 Waist Makers Declare Big Strike.” The New York Call, November 23, 1909. https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1909/091123-newyorkcall-v02n287.pdf.

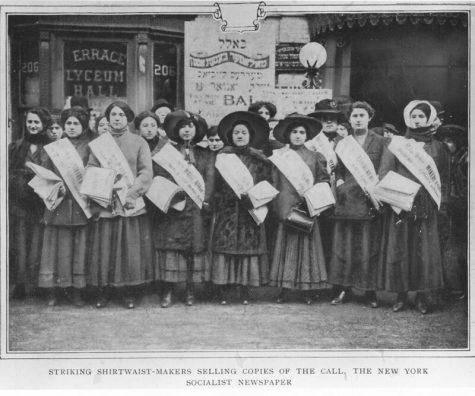

Dutcher, Elizabeth. “The Strikers’ Pickets. Defends the Volunteer Aids of the Shirtwaist Makers.” The New York Times, December 21, 1909. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1909/12/21/101751471.html?pageNumber=8.

“Shirtwaist Strikers Present Facts of Great Struggle To The Public of New York City.” The New York Call, December 29, 1909.

Magazine

Strunsky, Rose. “The Strike of the Singers of the Shirt.” In The International Socialist Review, 620-627. Charles H.Kerr & Company, 1910, 620-627.

Shari Belanger • May 27, 2022 at 8:56 PM

Thank you, Alysha. Beautifully done. When we were in the lower East Side of NYC over spring break, we happened to walk past the factory where this protest had occurred and there was even current messages in chalk written on the sidewalk. Thank you for educating us about this important event.