The opium pipe was beautiful, made of carefully crafted water buffalo horn and an artfully designed ceramic bowl. I was enveloped by its shine, smoothness, apparent tranquility. Much thought and love for the process of inanimate creation had gone into its production; it didn’t look like something to be afraid of, it only looked exquisite. On the base of the bowl, there was an inscription in metal chronicling the year 1868 or 1928. The conservators could not be sure which year it was referring to, but I can be sure that the forgetting of time is just one way the beast of addiction rears its ugly head, the date of the bowl’s conception lost in an opium-induced haze. On the top of the ceramic bowl were two painted images: one of a butterfly in bruised blue tones and the other of a poppy, the plant opium is made from, in a vivid orange hue. Though the butterfly was much larger on the bowl, the poppy with its disarming color took up more visual weight. This domination was to me symbolic of the control opioids have over people’s lives; the butterfly, bruised and battered, stood no chance against the malicious poppy. Suddenly, the art I had been looking at turned into something far more sinister. It was hard for me to reconcile the fact that the pipe could be both beautiful and destructive, and I found myself trying to separate the two halves of its existence. Yes, the opium pipe was beautiful. But it was also dangerous and cold, calculating. At the intersection of pain and beauty, the opium pipe nestled into my consciousness as I looked deeper into the exhibit.

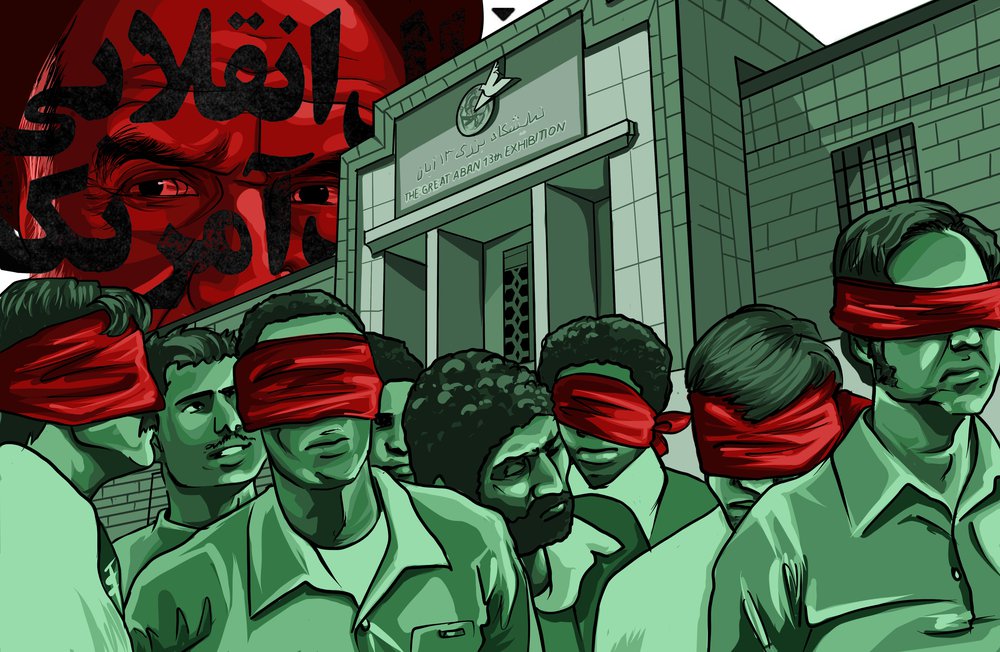

The exhibit was hosted by the Harvard Art Museum, which used it as a way to look inward at the museum’s own complacency in the Chinese opium crisis; Harvard benefited greatly from the spread of Chinese art into America that came with the crisis. During and after the First and Second Opium Wars, which broke out because of the West’s response to the growing Chinese opium industry, Chinese art was looted and sold into America, where Harvard would eventually gain access to it. A reputable institution, Harvard’s ivy-covered, storied buildings possess stolen and manipulated art. Even when searching for more information about Harvard’s complacency, I struggled to find anything. Instead of owning up to past mistakes, bad as they were, the institution preferred to wrap its indiscretions in carefully placed words and discussion of all the good they were doing with this exhibit. Again, I was at a crossroads; this time of Harvard’s purported perfection and the dark underbelly of its art collection. I had to quickly move on from this perplexing line of thinking, however, because my attention was being used primarily to comprehend the act of looking at art over a screen.

When I think of viewing art, I think of the humidity and distinct smell of museums put in place to protect the artworks. I think of hearing the hushed, echo-y tones of people talking around me that are so reminiscent of being in a cathedral. After all, to my secular mind, an art museum is not dissimilar to a cathedral in its vaulted ceilings and the sense of being near something far greater than yourself. But instead, I was in my poorly lit, somewhat cold room looking at a collection of pixels someone in Silicon Valley had ascribed meaning to. And it was quiet. The sound had been sucked from my room as I looked with intense focus at my computer. My screen, though capable of so much, could not place me in the exhibit and I was left with a feeling of incompleteness. I was merely a passive observer, able to look at the opium pipe but not to really, truly, experience it. For all my focus, all my fervent note-taking on a Google doc that took up the other half of my screen, I was incapable of being in the exhibit. Through the blankness of time and space stretching out from me in my room, I stared, transfixed, at the shiny- almost reflective- surface of the opium pipe and felt the strangeness of looking into a reflective surface and not seeing yourself. I could comprehend the horrors of addiction, but not the feeling of separation from what I was attempting to understand.

Growing up in Worcester, I had learned early the ways that addiction can dominate a person or place and how it harms all that it touches. Local police found piles of opioid medications and $200,000 in cash in my neighbors’ house a few years ago. My neighbors were always very nice, offering a “hello” if my family ever came across them on a walk. But we soon learned to pick out which cars were bound for that neighbors’ house by how fast they drove down our pleasant, residential street and we could tell who in the neighborhood park was there to buy drugs based on where they went and the way their eyes darted around the park. Now, that neighbor is in jail (for life). Now, people drive slower and the park is used by children and families more than dealers and addicts. Now, people do not walk up to my neighbor’s house and linger awkwardly at the doorway. I always wondered what they were thinking, those people whose addiction-controlled minds led them into an otherwise picturesque neighborhood to wait uncomfortably on a doorstep as families and dogs walked past. My neighbors, nice as they were, were doing something horrible to those people by fueling their addictions. It is hard to learn that no amount of waved greetings, neighborly conversations, or perfectly watered outdoor plants can prevent someone from being destructive to those around them; a ‘tough pill to swallow,’ as it were. From my own experience, I knew the personal side of addiction. So the opium pipe, seemingly removed from reality in its glass case that I viewed through a screen, was hard for me to fully understand without any people or physicality to give the context I so badly craved.

After my quest, I tried to feel content. I had completed the assignment; I could mark it as “done” in the portal. But it did not feel “done.” Unfortunate though it is, my quest left me wanting more. Seeing, but not experiencing, the beautiful yet destructive opium pipe and landing back in my own past, where I realized that my kind neighbors were neck-deep in nefarious activity that was actively harming people, left me feeling disconnected. I could not grapple with the two-dimensionality of it all, and to fill the gap, I started wondering. I wondered about small, concrete things such as, what was Harvard’s real intent behind putting up the exhibit? And, why was it only temporarily in-person? I was eager to look further into my unanswered questions about the spread of Chinese art and opium into America and the institutions that allowed for it, as well. But I also wondered about more abstract things that I can only imagine delving deeper into such as, what is art? (I know, pretty clear-cut.) The opium pipe I viewed went from being a beautiful but utilitarian object, to being a mournful object that is considered art. What made this switch? Was the opium pipe always, never, or somewhere in between, art? I can close my computer, stand up from my chair, and leave my room, but the questions brought upon me by my quest will always linger in the back of my mind, reminding me that there is always more to be done and thought about.

Photo by Václav Pluhař on Unsplash