After three decades of conflict and violence in Northern Ireland, how can the nation reunite and make peace? This question was heavily debated in 1998 when the thirty-year conflict known as “The Troubles” ended with the Good Friday Agreement, and it persists today as new circumstances have arisen since the agreement’s development. Issues such as Brexit, or the United Kingdom(UK) leaving the European Union(EU), the continued religious divide, and several government shutdowns call into question whether the Good Friday Agreement is sustainable or if it only served as a short-term solution for immediate relief and structure after ending the conflict. Northern Ireland is still accounting for damages caused by the Troubles with political, social, and economic reform policies. Twenty-five years later, Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement was only a short-term solution, failing to serve long-term peace.

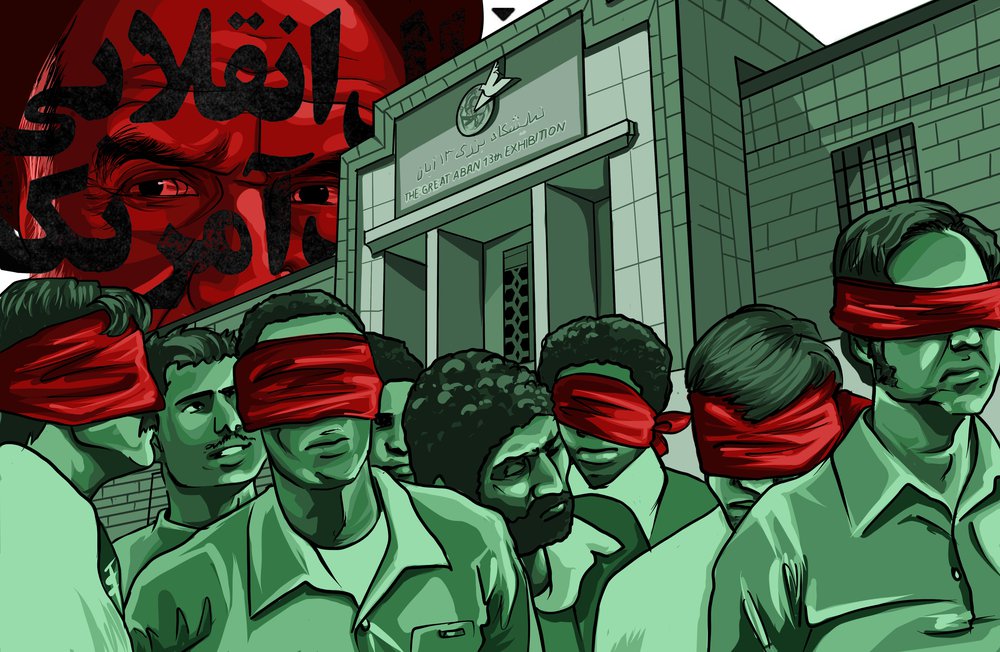

On July 14, 1969, a Catholic man was beaten to death in Northern Ireland by Protestants for protesting against the discrimination of the Catholic minority(McGee). This death was only the first out of many casualties in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, lasting from the late 1960s to 1998. The division between Catholics and Protestants began long before “The Troubles,” however. In 1169, through the “plantation program,” Catholics’ land was taken by the British and given away to Protestants(Mitchell 89). This initial conflict perpetuated for centuries, causing the British in 1920 to partition Ireland into Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and leaving the Catholic population in Northern Ireland a minority(Mitchell 90). When Catholics protested for equal treatment in the North, they were suppressed and faced violence by paramilitaries in 1960(Mitchell 90). As several years passed, paramilitaries realized violence was not an effective way to exact change and sought a peace deal(McGee). A final agreement reached in 1998, known as the Good Friday Agreement, putting in place a power-sharing assembly for the unionists(pro-British) and the nationalists(pro-Irish), permitting a ‘soft’ border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, and disarming the paramilitary groups to end the violence of “the Troubles”(McGee).

The Good Friday Agreement failed because the power-sharing assembly resulted in a lack of compromise between the opposing parties and the government’s shutdown. Through the agreement, a power-sharing assembly was introduced to give a voice to the Unionists and Nationalists, currently known by their political party names, the Democratic Unionist Party(DUP) and Sinn Fein, respectively(McCormack). However, giving both parties an equal hand in the government created strong opposition without any allowance for mediation. As the parties clashed together several times, Northern Ireland’s government faced suspension in 2017 and the DUP themselves left the assembly in 2022(“Northern Ireland”). Without an assembly, Northern Ireland’s civil servants took control, but they could not carry out policies for further necessary reform(McCormack). Although the DUP eventually returned to the assembly in 2024, their ability to simply walk away from the government and not cooperate showcases the fragility and weakness of Northern Ireland’s government(“Northern Ireland”). The political failure of the agreement may have been a direct result of its basis being the divide between Catholic Nationalists and Protestant Unionists. This assembly required unity among both parties to succeed but instead encouraged separation, resulting in severely polarized ideologies.

The Good Friday Agreement was a failure because segregation and a systemic divide between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland continue today. Discrimination against Catholics was deeply rooted in the plantation program centuries earlier and grew during the Troubles with violence caused by paramilitaries(Mitchell 89). Through the Good Friday Agreement, those paramilitary groups were decommissioned to end the violence, but segregation between Catholics and Protestants continued (McGee). Today, peace walls, or physical barriers, remain to separate the religious groups from one another to ensure that violence does not escalate between them again (“Northern Ireland”). Many people in Northern Ireland still do not feel safe without the peace walls (“Northern Ireland”). Going to the lengths of building walls and fences to segregate groups of people reveals how easy it is for the violence that broke out once during the Troubles to restart. In Northern Ireland’s education system, schools remain approximately ninety percent segregated. Failing to integrate students because of their differences, Catholic and Protestant schools can teach two very different versions of history that may be biased according to their religion, hearing that one side is “evil” and installing baseless prejudices in young children’s minds (Magee). This systemic divide paves a possibility for extreme violence in the future based on religion because the Good Friday Agreement failed to account for the separation.

Due to the rise of border conflict between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland after Brexit which negatively impacted trade, the Good Friday Agreement failed. Through the agreement, a ‘soft’ border was established between the two countries where people and goods could cross without security checks because Northern Ireland and the UK were both part of the EU (Mitchell 93). In 2020, Brexit took place, and the idea of a ‘hard’ border came into question, causing tension over whether the terms of the agreement would be upheld (Farry). To combat this, in 2021, the Northern Ireland Protocol was established to secure the ‘soft’ border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and ensure no security measures on the border could disrupt trade (Fleming). Instead, there would be security between Northern Ireland and Britain on the Irish Sea Border (Hayward and Phinnemore). Trade from Britain to Northern Ireland would fall under the rules of the EU’s market such as paperwork for certain imports and exports(Fleming). With those new trading circumstances, tensions rose because of new regulations and manufacturers who held back productions, allowing prices to rise(Hayward and Phinnemore). With new regulations, trade needed to be properly reviewed by the power-sharing assembly, but the political parties found it challenging to compromise on post-Brexit negotiations and thus economic reform was paused (Hayward and Phinnemore). While strides have been made to control the economy despite Brexit, the border turmoil that rose in Northern Ireland from Brexit makes the agreement a failure as it lacks political-economic compromise.

The Good Friday Agreement failed Northern Ireland because of their government’s instability, persisting religious divide, and resurfacing border conflict after Brexit. While the agreement ended violence and provided a government to give the nation some form of stability after the Troubles, true reconciliation and long-term success rely on the people themselves and how they interact with those who are different from them. The basis of the Northern Ireland conflict lies in religious separation that runs systemically, and it infiltrates into all aspects of the nation. While a nation requires time to heal after an intrastate conflict, failure to address the underlying problem causes the country’s politics, society, and economy to be so fragile, that with the snap of fingers, violence could escalate back to the Troubles again.