When discussing the most defining moments in human history, the colonization of Africa must be brought up. The instant Europeans set foot on African soil, the world was forever changed. Colonization’s ugly shadow follows us, both oppressor and oppressed, constantly. It permeates every aspect of our lives; governance, employment, justice. To combat these impacts, we as humans must understand colonization, not just know it. To know something is to see it from the surface, to be blind to its depth and dimension. But to understand something is to allow it to consume one’s thinking, completely changing what was there before, in the knowing. To do this, to really understand anything, is a monumental task, but thankfully there are resources to help. Chief among these resources is the book Things Fall Apart, a story of colonization told through the eyes of the Ibo people before and during European missionaries’ attempts to convert them to Christianity. This book is well worth the read. It still carves out a space in the annals of literature 70 years post-publication by standing strong in its brutal honesty, uniqueness, and relevance.

Though it is a great book, Things Fall Apart is at times very difficult to read. Violence is a constant in this book, which does not come as much of a surprise: violence is a constant in life (sad as it is to say), and certainly in colonization. From the first page, we are shown the normality of violence: “Okonkwo threw [Amalinze the Cat] in a fight which the old men agreed was one of the fiercest” (Achebe 1). And, while the number of all wars throughout history is near innumerable, the Geneva Academy reports that the number of wars currently occurring is 110 (Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights). This is a truly massive number and shows how common violence is in our lives. Chinua Achebe understood this when he wrote this book, and utilized violence as an outlet for authenticity. As someone who reads a lot, I find inauthentic books easy to sniff out but hard to read. When an author tries to take a story that is not theirs, or uses a story to communicate something it was not meant to, the book becomes inauthentic, a caricature of a story. Things Fall Apart, though, is nothing if not authentic. It does not try to glorify anyone or anything, instead exposing the reader to all aspects of Ibo life and European colonization. This is often done by using violence, as throughout the book the reader is exposed to violence without justification. There are many different types of violence in this book, and they are all received by the community very differently. Violence between men within the tribe is highly frowned upon, unless it is during a wrestling match or war. Hurting (or killing) a man for sport or to protect the tribe is good, as said explicitly in the book, “In Umuofia’s latest war [Okonkwo] was the first to bring home a human head. That was his fifth head; and he was not an old man yet” (Achebe 10). On the other hand, Okonkwo accidentally killing another member of the community via malfunctioning gun is bad and results in his exile. Violence committed against women isn’t exactly encouraged, but it isn’t discouraged either. Okonkwo brutally beating his wife during the Week of Peace is bad (it interfered with tribal customs), but Okonkwo beating his wife during any other part of the year is fine, which is pointed out as early as chapter two: “His wives, especially the youngest, lived in perpetual fear of his fiery temper, and so did his little children” (Achebe 13). No one in the community loses any respect for Okonkwo, even though he treats his family in such a way.

But, there is one more type of violence seen between Ibo people in Things Fall Apart, though it is not brought up until the end: violence against the self. After seeing that there is no hope to combat the missionaries, and that he is losing his people (things are falling apart, as it were), Okonkwo kills himself. It happens suddenly, with little warning. Okonkwo is (was) a prideful man. He tries (tried) as hard as he could to preserve the customs of his tribe. He knew that killing himself was an abomination against the Earth, yet he did it anyway. The dichotomy between Okonkwo’s pride and the way his life ends is stark, and is seen by his best friend Obierika, who says to the District Commissioner: “‘That man was one of the greatest men in Umuofia. You drove him to kill himself; and now he will be buried like a dog…’ He could not say any more” (Achebe 208). Okonkwo’s death and Things Fall Apart are both cries against the evils of colonization, often brutal in their emotion. This makes Things Fall Apart very difficult to read. It is rife with deep, painful, conflict that the reader is not spared from. But this has its upsides: honesty, of course, and the trust built between reader and author. Once the reader understands that the author is telling them the truth, not just a version of it, they can finally relax into the book and learn from it. The reader is brought to this understanding through Achebe’s criticism of the violent systems that are present not only in colonialism, but also in Ibo society. This is incredibly honest: admitting wrongdoing. It is hard to do and to read, but is important nonetheless. This is one of the ways in which Things Fall Apart is a uniquely educational book and is why its lessons can be learned through no other book.

As an avid reader, I have read many, many books over the course of my life. I have even begun keeping track: last year, I read 30 books; this year, I’ve read 12 so far. Within these, quite a few books have been about colonization. I try to stay informed, especially as someone who has benefited from colonization, and I honestly find the topic interesting. But, there was a hole in my knowledge and bookshelf, a hole shaped exactly like Things Fall Apart. Until reading this book, I did not realize how America-centric my books were. Why would I? I am American, after all. Sure, I read books about people in other countries, but the countries they’re in don’t often play a major role in the trajectory of the story. So, I had been reading largely one type of book for my whole life. In the books about or relating to colonization, its importance was really only mentioned as it related to America. The books only described what happened after people were brought to America and enslaved, they did not describe the people’s lives before leaving their homeland. Even in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (a book about the history of oppression and oppressed people in the United States. Its title is pretty descriptive), the narrative focuses only on what happened after colonization. On the other hand, Things Fall Apart takes place just before and during colonization; it does not mention the “after.” In doing this, the reader is taught a huge amount about Ibo people and their culture, a type of exposure rare in Western literature.

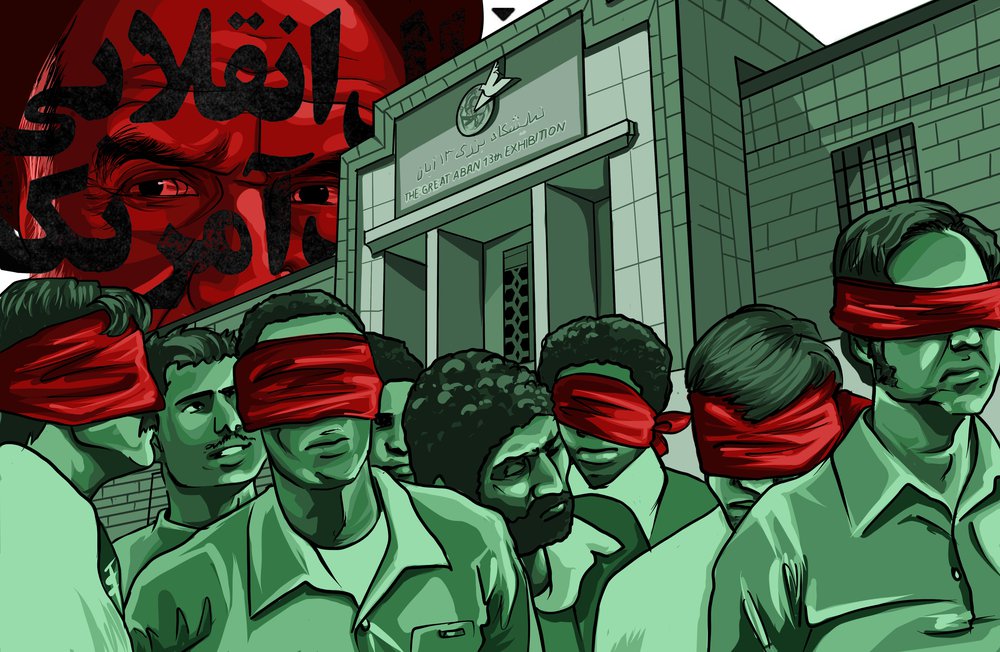

Things Fall Apart was written 66 years ago, and takes place 130 years ago. Many people, understandably, do not want to read books about and from so long ago. These books can be difficult to get through and have messages that are not applicable today. So, why should Things Fall Apart still be held to such high status, and treated with such relevance? Well, Things Fall Apart was (and still is) groundbreaking, especially during a time in which racism was so rampant. This is perfectly encapsulated by Ruth Franklin, who wrote, “Western reviewers praised Achebe’s detailed portrayal of Igbo life, but they said little about the book’s literary qualities. The New York Times repeatedly misspelled Okonkwo’s name and lamented the disappearance of ‘primitive society’” (Franklin). These reviews are clearly horrible and deeply racist. To describe any non-Western society as “primitive” is completely inexcusable, and the supposedly positive reviews aren’t much better. Glossing over Achebe’s literary talent is also an awful thing to do, especially when it is done to prop up incorrect beliefs about colonization. Unfortunately, we have not strayed far from the norms of this time. Racism still gets excused, and is still encoded in the fabric of our country. This is perhaps best shown by America’s “justice” system, where nearly 40% of prisoners are Black (Federal Bureau of Prisons), though Black people make up less than 14% of the American population (United States Census Bureau). Things Fall Apart has remained relevant because the colonialism it describes is the same colonialism seen today, in America and all over the world. Chinua Achebe himself says it best, “I didn’t know how other people elsewhere would respond to it. Did it have any meaning or resonance for them? I realized that it did when, to give you just one example, the whole class of a girls’ college in South Korea wrote to me, and each one expressed an opinion about the book. And then I learned something, which was that they had a history that was similar to the story of Things Fall Apart—the history of colonization” (Bacon 2000). Colonization is a shared history, from West Africa to East Asia. Things Fall Apart gives people who have long been ignored or delegitimized by the West a voice. This is exactly why it is still important, and why it will continue to be. If all lessons to be learned from Things Fall Apart had in fact been learned, the book would become obsolete on its own. But, clearly, this is not the case. This book has stayed at the forefront of our collective consciousness since its publication, meaning that we have much more to learn and do. To read Things Fall Apart is to be a well-rounded, learned global citizen and to broaden one’s knowledge in ways that would otherwise be impossible.

Things Fall Apart taught me a great deal, both from reading it and from in-class discussions. From reading it, I learned how “things” really began to “fall apart,” especially with regards to Ibo cultural norms becoming the undoing of Ibo culture. For example, ostracized people were many of the first to leave their tribe for the church, “These outcasts, or osu, seeing that the new religion welcomed twins and such abominations, thought that it was possible that they would also be received” (Achebe 154). It is a great irony: the Ibo people wanted riddance of those not worthy of being in their tribe until those people joined another group and forsook their Ibo-ness. From class discussions, I learned how father-son relationships can stay the same over generations, though they take different forms. This was especially true of the relationships between Okonkwo and his father, and Nwoye and Okonkwo, “And so Okonkwo was ruled by one passion- to hate everything that his father Unoka had loved” (Achebe 13), compared to “But he left hold of Nwoye, who walked away and never returned” (Achebe 152). In both of these examples, we can see a son trying his best to distance himself from his father. While this may seem clear, it was not for me until I heard it from someone else in a class discussion. Yes, this learning was fascinating, but no, it was not difficult to do. Things Fall Apart is written to guide the reader, to teach. This is what makes it so distinct from other books: it is educational without being oppressively so. I would hazard a guess that most people do not read textbooks for fun (call me crazy) even though textbooks are incredibly educational. Things Fall Apart can teach just as much and as well as any textbook, and it is a truly enjoyable read.

Is Things Fall Apart important? Is its prose worth sharing, worth caring about for generations to come? Sure, books hold meaning, but how much does the meaning matter? On a case-by-case basis, this is difficult to answer. “Meaning” is broad. It is different for everyone, which is what makes it so special. For people to see and appreciate the meaning of a book is a cosmic feat so powerful, it has the ability to change lives. Is this true of Things Fall Apart? Yes. Absolutely, yes. In one sense, this book is about one group of people during one time period in one place. But in another, truer sense, it is about all people during all times in all places. We only need to look to the title of the book to see our first clue that this book is about all of us. “Things Fall Apart.” This refers to Okonkwo, the Ibo people, Africa, the world. The world was falling apart in 1898, when the book was set. It was also falling apart in 1958, when the book was published. It is still falling apart now. We, humans, must learn from our mistakes by reading this book. Through Things Fall Apart, we see so many perspectives, so many flaws and perfections. There is much still to be learned from this book that can not be learned from any other. So, we should all read it. Why not? We can all learn a thing or two from it, and this learning is easy to do. Things Fall Apart is a hugely important book, and it should be read by everyone due to its authenticity, uniqueness, and continued relevance.

Works Consulted

Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights.

geneva-academy.ch/galleries/today-s-armed-conflicts. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Penguin Books, 1959.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. HarperCollins, 1980.

Federal Bureau of Prisons. www.bop.gov/about/statistics/

statistics_inmate_race.jsp. Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.

United States Census Bureau. www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045223.

Accessed 31 Mar. 2024.