Sanctions and Stalemates

The 1979 Iranian hostage crisis not only redefined the internal narrative of Iran by reinforcing already popular anti-Western ideology, but also prompted significant economic challenges and long-term diplomatic isolation that affected Iran’s relationship with the United StatesUnited States. When 52 Americans were taken hostage by a group of Iranian students at the U.S. embassy in Tehran, multiple economic attacks were placed by not only the U.S. but countries all over the world that launched Iran into major economic setbacks and deprived them of essential resources. The hostage crisis was an event that would mark a turning point in Iran’s history and would set off a chain reaction of political and economic shifts that would influence and shape the future for Iran.

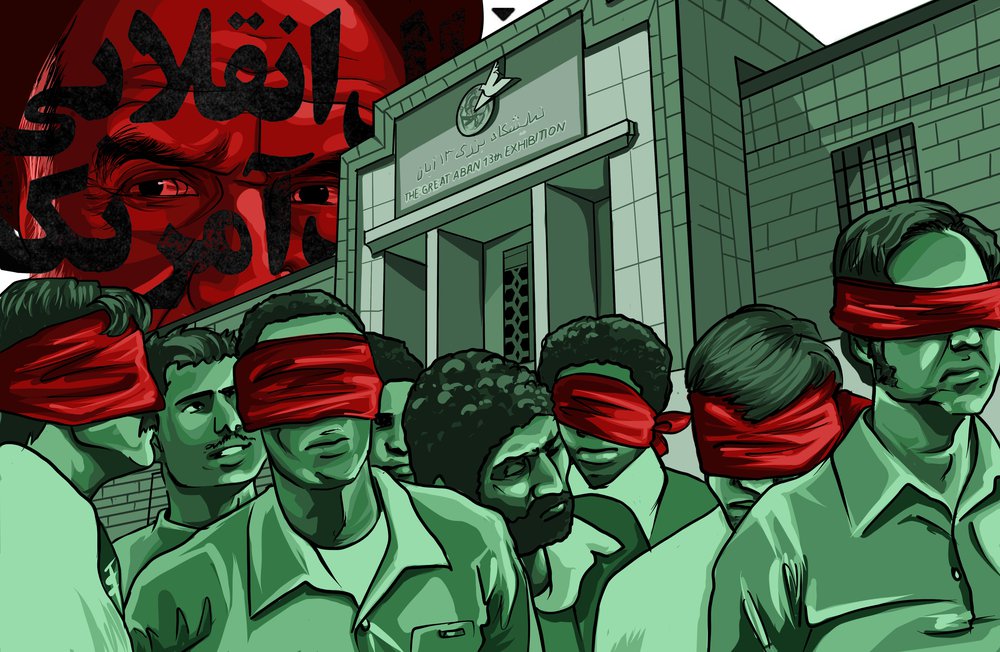

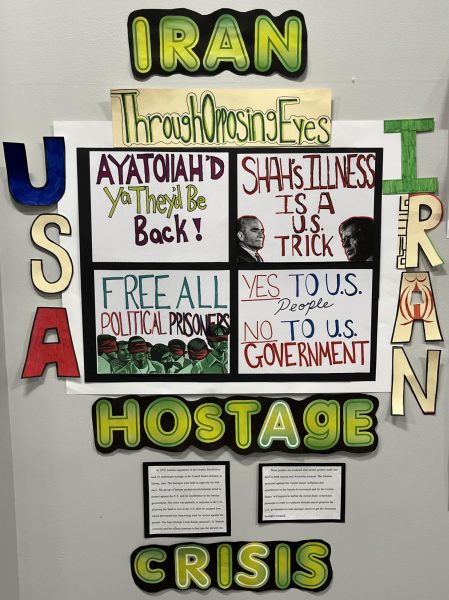

In Tehran, Iran on November 4, 1979, a group of Iranian students broke into the United States embassy taking 52 people hostage inside of the embassy. Ebrahim Ashazedeh, one of the students who took over the embassy, was the main mastermind behind the takeover. Ashazedeh consulted with heads of islamic associations of Iran’s main universities while creating his plan. He formed the group known as The Muslim Student Followers of the Imam’s Line which was the group of students who helped him carry out his plan.The students were followers of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, an Iranian religious and political leader who was known for his anti-western views and his opposition of the pro-western regime of the Shah. He was exiled in 1964 and though he was away from Iran, he still had influence within the country that he used to urge his followers to overthrow the Shah (BBC History). The students who were loyal to and still followers of Khomeini held a demonstration outside of the embassy the morning of the occupation. The students made it clear that their actions wouldn’t be a big deal by holding signs that read “don’t be afraid, we just want to sit in.” Their main purpose that day was to object against the U.S. Government by occupying the embassy for multiple hours while they announced their protests from within the compound. The longest they intended to hold the hostages was for a couple days but, with the outstanding amount of support from the Iranian people and Khomeini himself, they changed their plan (Watson). The hostage crisis lasted for 444 days until January 20, 1981 and ended with the negotiations between the U.S. and Iran with Algeria acting as the mediator. The creation of the Algiers Accords were the final part of the negotiations ensuring peace between the two countries.

On August 19, 1953, both the United States CIA and the British intelligence agencies assisted the Iranian military to carry out a coup with the goal of overthrowing Iran’s prime minister, Mohammad Mossadeq. The origin of the coup began with Mossadeq’s nationalization of the British owned Anglo-Persian oil company which prompted London to pose a trade restriction for oil on Iran (Council on Foreign Relations). The U.S. seemed afraid that they would lose Iranian crude oil to the Soviet Union which is the reason they opted to participate in the take over (Karimi and Gambrell). The coup ended with the U.S. and Great Britain instating Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as the Shah of Iran who was known for supporting western ideology and could in the future act in favor for both the U.S. and Great Britain. The U.S. then widened their sphere of influence and had some control over the inner workings of Iran which was of great benefit to them. But, the interference of these outside powers prompted anger within the Iranian people that fueled the already established Iranian revolution. The people of Iran did not want to be a pawn used by the United States in their game when they didn’t have any business interfering in the first place. The people of Iran liked their typical Middle Eastern traditions and practices so when the U.S. came in and disrupted their customs, it did not sit well with the people who were actually affected by the change. Iran’s opinion of the U.S. to this day is that the U.S. can not be trusted. This one event affected and stayed with Iranians for so long that even today “Death to America” can still be heard in their prayers.

When the United States learned of the hostage crisis in their own embassy, they had to respond in some way that wasn’t just giving in, and the answer was sanctions. Sanctions are economic and political measures that aim to influence the behavior of a state, group or individuals. Sanctions can be introduced in an attempt to change the policies of a state that threatens international peace and security (Government Offices of Sweden). At the time of the hostage crisis, President Jimmy Carter was in office and had decided that the U.S. had to take action after the hostages were taken. He chose to place sanctions because they were brutal enough to intimidate Iran and motivate them to release the hostages but also a warning that at any point President Carter could make the situation a lot worse for Iran economically. After U.S. sanctions were placed on Iran, multiple countries such as Mexico, Austria, and China decided that they would place countering sanctions against the U.S. to try to help regulate the economic impact on Iran. The countries that did not take initiative against Iran cautiously joined the U.S. in pressuring them. Many countries treaded lightly due to the fact that Iran was a major oil exporter, and they feared that they would be cut off from a major energy source. The Japanese government was an exception to the uneasiness of other countries, they decided to cease all oil imports from Iran as the crisis grew more urgent with other European countries following in Japan’s footsteps. Most countries chose to do this by reducing financial and diplomatic relations with Iran. Australia decided to take a step further by placing a trade ban on all goods that were not food products such as medicine (Hewitt and Nephew). Both Japan and Australia were major players in creating economic stress for Iran, influencing other countries to act in similar matters, placing economic sanctions and banning imports from Iran. These sanctions proved to be functioning in their intended ways by hitting the Iranian economy hard with trade falling quickly. U.S. imports went from 3.7 billion dollars to 23 million dollars in a matter of months. An estimate of the total economic cost to Iran shows that from 1980 to 1981 the total was 3.3 billion dollars.

After the end of the hostage crisis, the relationship between the U.S. and Iran evidently became strained. On April 7, 1980, President Jimmy Carter officially announced that the United States would be breaking off diplomatic ties with Iran as a direct result of the hostage crisis. This meant that all embassies and consults in Iran were to be closed and that diplomatic personnel had to leave the country immediately. In a statement, the U.S. Department of State criticized the Iranian government for “hiding behind the militants at the embassy” and not doing anything to aid or expedite the situation. An act further scrutinizing Iran was also outlined invalidating Iranian visas issued to Iranian citizens for future entry into the United States. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, there was an obvious clash in political ideology between the two nations with the revolution transforming Iran into a theocratic republic that altered Iran’s foreign policy outlook. The new regime viewed the U.S. as imperialist and when it came to negotiations for the hostages, refused to engage in direct negotiations forcing the U.S. to rely on a third party, which further showed the tensions and built up mistrust between the two countries (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History). Even after the release of the hostages, the relationship between Iran and the United States has remained unsteady. The U.S. embassy remains closed in Tehran while Iran continues to portray the United States as a hostile force in their political sphere. This long-lasting break in relations not only affected U.S.-Iran ties but also impacted America’s overall approach to the Middle East, creating lasting tensions, missed chances for communication, and significant mistrust that is still present today.

The Iranian hostage crisis of 1979 was a pivotal event that deeply impacted the relationship between Iran and the United States. The crisis not only intensified Iran’s already established anti-western ideology but also prompted for a series of economic sanctions that strained the Iranian economy and led to extensive diplomatic isolation. The events surrounding the hostage crisis and the effects that followed cemented mistrust and hostility between the two nations for decades. As a result, the crisis launched a chain of political and economic shifts that have continued to influence relations between the U.S. and Iran, reinforcing the long-term effects of sanctions and the stalemates that came from them on both countries and their future interactions.

Works Cited

AL Jazeera. 11 Feb. 2014, www.aljazeera.com/features/2014/2/11/iran-1979-the-islamic-revolution-that-shook-the-world. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.

“Ayatollah Khomeini (1900-1989).” BBC, www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/khomeini_ayatollah.shtml. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

“Breaking Diplomatic Ties with Iran during the Hostage Crisis, 1980.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/breaking-diplomatic-ties-iran-during-hostage-crisis-1980. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.

Department of State. “The Iranian Outlook and the Hostage Crisis.” Archives.gov, 2 Dec. 2016, www.archives.gov/files/declassification/iscap/pdf/2015-071-doc27.pdf. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.

“A Freeze in Relations.” Cold War Reference Library, edited by Richard C. Hanes et al., vol. 2, UXL, 2004, pp. 319-45. Gale in Context: World History, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3410800038/WHIC?u=mlin_c_bancsch&sid=bookmark-WHIC&xid=9fdc0e98. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025.

Hewitt, Kate, and Richard Nephew. “How the Iran Hostage Crisis Shaped the US Approach to Sanctions.” Brookings.edu, 12 Mar. 2019, www.brookings.edu/articles/how-the-iran-hostage-crisis-shaped-the-us-approach-to-sanctions/. Accessed 17 Apr. 2025.

“Iran Hostage Crisis.” Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran_hostage_crisis. Accessed 4 Apr. 2025.

Karimi, Nasser, and Jon Gambrell. “A CIA-backed 1953 Coup in Iran Haunts the Country with People Still Trying to Make Sense of It.” AP News, 25 Aug. 2023, apnews.com/article/iran-1953-coup-us-tensions-3d391c0255308a7c13d32d3c88e5f54f. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

Majid-Majid, Abdol. “Iran 1980-85: Problems and Challenges of Development.” Jstor.org, July 1977, www.jstor.org/stable/40394996?oauth_data=eyJlbWFpbCI6Imxhc3RhcmppYW4yMDI2QGJhbmNyb2Z0c2Nob29sLm9yZyIsImluc3RpdHV0aW9uSWRzIjpbIjhkYzRkZjA0LWZmZDAtNDY4Yy1hZWE5LTBhMjNlYTA4M2I4OSJdLCJwcm92aWRlciI6Imdvb2dsZSJ9&seq=3. Accessed 14 Apr. 2025.

“Timeline: U.S. Relations with Iran.” Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/timeline/us-relations-iran-1953-2023. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025.

United States, Congress, Department of State. The Iranian Outlook and the Hostage Crisis. Archives.gov, 17 Apr. 1980, www.archives.gov/files/declassification/iscap/pdf/2015-071-doc27.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025. Document ISCAP APPEAL NO. 2015-071, document no. 27.

DECLASSIFICATION DATE: December 02,2016

Watson, Stephanie. “Iranian Hostage Crisis.” Gale in Context, edited by Brenda Lerner, 2004, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3403300410/UHIC?u=mlin_c_bancsch&sid=bookmark-UHIC&xid=efb798a4. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

“What Are Sanctions?” Government Offices of Sweden, www.government.se/government-policy/foreign-and-security-policy/international-sanctions/what-are-sanctions/. Accessed 24 Apr. 2025.